When you work in a Locktender’s House, you are constantly reminded of the people who once lived here and worked the lock so many years ago. We know from first-person accounts that lock tending was a demanding, low-wage job. One main benefit was free housing. And back in the day, “free” didn’t get you much.

There were 23 locks along the Delaware Canal, and 17 Locktenders were initially employed to ensure the canal boats could travel through the locks as efficiently as possible. Several sections of the Canal required adjacent locks to accommodate the drop in elevation. In those instances, a Locktender was responsible for two closely situated locks.

An example of this could be found in New Hope, where Locks 8 & 9, along with a guard lock were the responsibility of one Locktender. The same was true of Locks 10 and 11. In New Hope, you will find three Locktenders’ houses within less than ½ mile.

The original list of Locktenders included*:

- John Hibbs – Lock 1 and the Tide Lock

- Elias Gilkyson – Locks 2 and 3

- Samuel Daniels – Locks 8, 9, and Guard Lock in New Hope

- Samuel Stockdan – Locks 10 and 11

- George Solliday – Locks 13 and 14

- Mahlon Smith – Locks 15 and 16

- Joseph Shepard – Locks 22 and 23

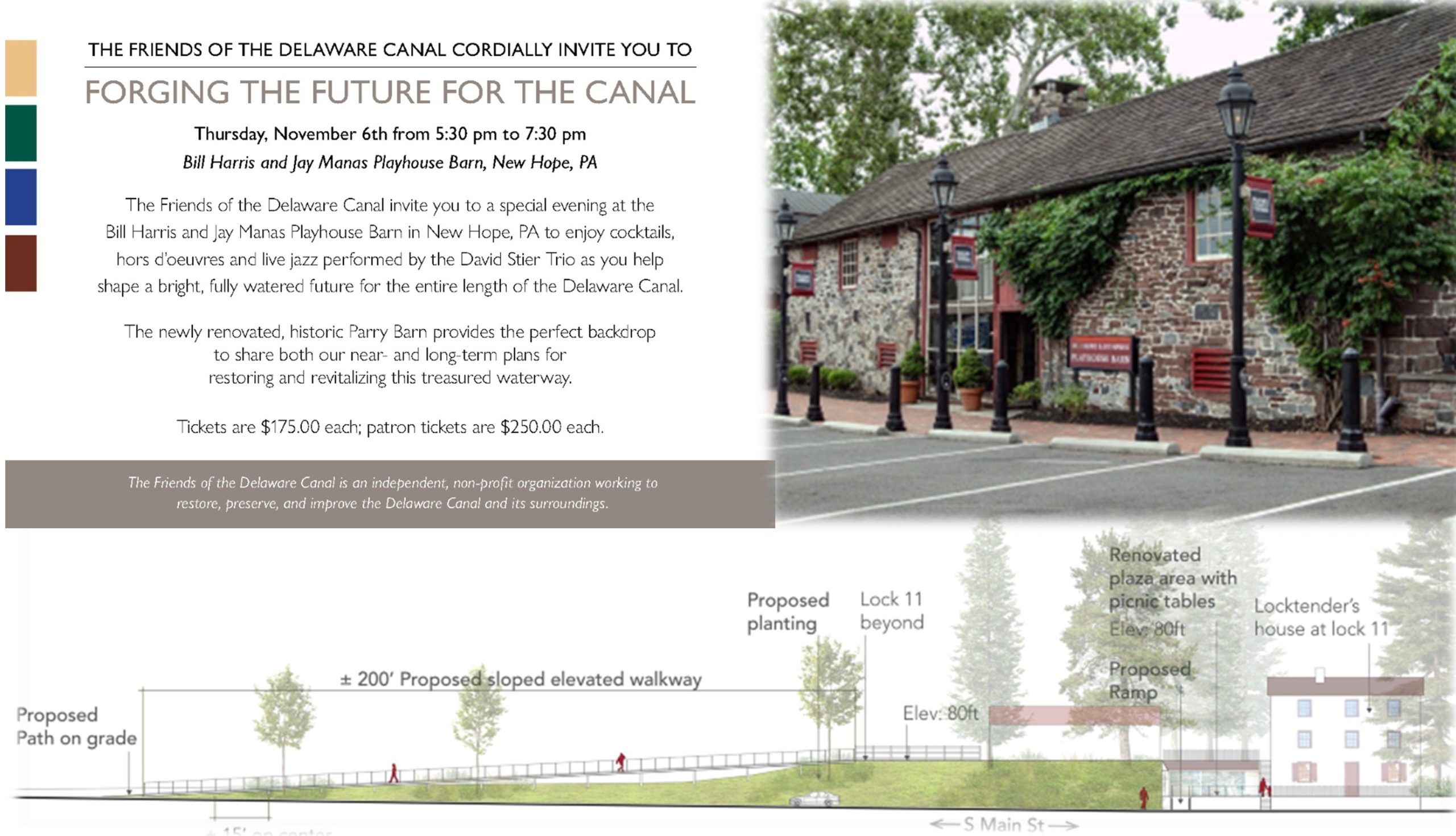

Lock 11 and the adjacent house serve as the headquarters of the Friends of the Delaware Canal. This house is still a mystery. Research indicates that the building pre-dates the construction of the Canal and was likely built by Lewis Coryell, who owned the land and worked as the engineer on this section of the Canal. The original first floor of the structure is now underground. The street elevation was raised at some point, and the first floor was filled in.

Dawn to Dusk

The workday of the boatmen and Locktenders began before dawn, and it lasted well into the night. During the height of canal activity, Locktenders became very efficient at locking boats through. And with the help of a willing boat crew, the task could take three to four minutes.

As the canal boat captain signaled their approach, the Locktender would be ready to guide them through. The captain would throw a line with a loop at the end, which the Locktender would attach to a cleat on the lock. The captain would then “snub” or tether the boat before hitting the lower gate.

As the boat sank, the captain would release the line. The boat would sink to level and continue the journey.

Heavy traffic was managed by locking distance markers which were guideposts placed a hundred plus yards away from the lock in either direction. The rule is that you could proceed if you were in the locking distance before another boat.

However, the Locktender had discretion here. If the lock were ready for a boat coming north, the boats traveling in the opposite direction would need to wait. The widening of the locks helped ease the captains’ tension, who were eager to get on their way. These locks allowed two boats to lock in simultaneously and improved overall traffic flow in the busiest sections of the Canal.

At night, the Locktender would signal that the gate was open by waving a lantern. If the lock was closed, a ruby-colored lamp would be placed in the window of the wicket shanty. When the Canal opened, the boats traveled day and night, leaving no rest for the Locktender. By the mid-1850s, however, this changed, and Locktenders worked from 4:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. every day except Sunday.

Since the Locktenders were responsible for keeping the traffic moving, they became very

adept at anticipating oncoming traffic. Once they heard the sound of the approaching boat, which could be a bugle or a conch shell, they would reply with their own response to indicate whether the lock was open or closed. Boat captains were always in a hurry. The more trips they made, the more money they made, so in general, they were an impatient crowd. Fights over who could lock in first were a daily occurrence in the early years. And stories tell us that Locktenders were sometimes forced to throw the brawling parties into the Canal to cool off tempers.

A Family Affair

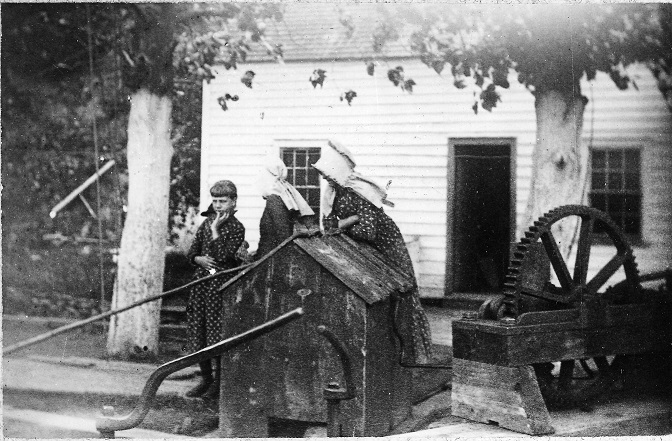

A Locktender wasn’t paid much, so they often had to supplement their income by taking other jobs during the day. This meant the whole family was put into service, locking in the boats as needed. One source said that as soon as a child was strong enough to work the wickets, they were “hired” for the job.

Many Locktenders and their wives also earned extra money, supplying boatmen with provisions. Often, these industrious families would grow vegetables and some livestock, if they had the room, and would sell or barter with the boat captains. Some wives would sell baked goods and launder clothes. Still others would provide stable space for mules to rest in the evening. Boatmen gave these houses names such as the laundry lock or the mule barn lock.

Locktender Houses

According to research from the Heritage Conservancy, 16 Locktender’s houses were built along the Delaware Canal for $9,200.46. These houses were small but well-built. Most were constructed with stone. However, storms and floods led to the rebuilding of many original structures along the Canal. All but one house was built before electricity became available.

Most houses were two stories with two rooms downstairs and a kitchen. Upstairs there would be two or three bedrooms. The bathroom was usually an outhouse. And not surprisingly, they were heated with coal, which was often traded or purchased from canal boat captains. Any land adjacent to the house was put to good use. Gardens, chickens, and even some larger livestock helped feed the family and the passing boatmen. Without this supplemental income, most families could not survive.

A Living Legacy

Like many historic sites, several Lockhouses have been lost to time. However, some still remain. Several are used by the park service, including our headquarters, yet others are now private residences.

When it became clear the Canal would be sold to the State of Pennsylvania, the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company offered to sell the Lockhouses to company employees. One account was discovered and shared by a FODC member who is fortunate to live in a Locktender’s house today.

As you can tell from the following letter, these Lockhouses were prized for their location and historical connection. Today, the current owners lovingly maintain the character and charm

Excerpts from a letter to the homeowners (dated 8/5/1978).

“It may be of some interest to you to know some of the history (albeit recent) of the Lockhouse. My father was an official of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, the builders and operators of the Canal, and at the time of the transfer of the Canal (late 1920’s) to the Commonwealth, he was able to purchase one of the lockhouses. The one chosen was to be a weekend retreat as well as a vacation site, and it seemed that (this one) was the best of the lot as well as the most scenic.

When we took it over it was, to put it mildly, a pigsty. The house itself was filthy and the entire property looked as though it had not been cleaned since the Canal was originally built. The small building in the back, toward the River Road, was located on the cement pad next to your house and we had it moved to its present location and installed some sanitary facilities, inasmuch as the purchase price included a half-moon backhouse, which did not appeal to us.

Needless to say, for quite a few years, our weekends and

vacations were spent in trying to humanize the house and grounds. However, there was compensation: Quite a few parties were held which the family and friends enjoyed. I remember having my high school pals, as well as gals, for weekend shindigs. (In the 30’s, believe me, they were properly chaperoned.)

In the northeast corner above the lock, we had installed a dock at which we kept two canoes and a rowboat because at the time the aqueduct over the Tohickon had not been demolished and we were able to canal for miles north on the Canal.

The original cost to my father for the property, as I remember, was $500.00. Due to World War II, the gasoline shortages, and the fact that sons were called into the service, as well as the death of my father in 1937, the property was sold in 1943.”

*Source: A complete list of the original tenders can be found in the Delaware Canal

Journal by C.P. Yoder.